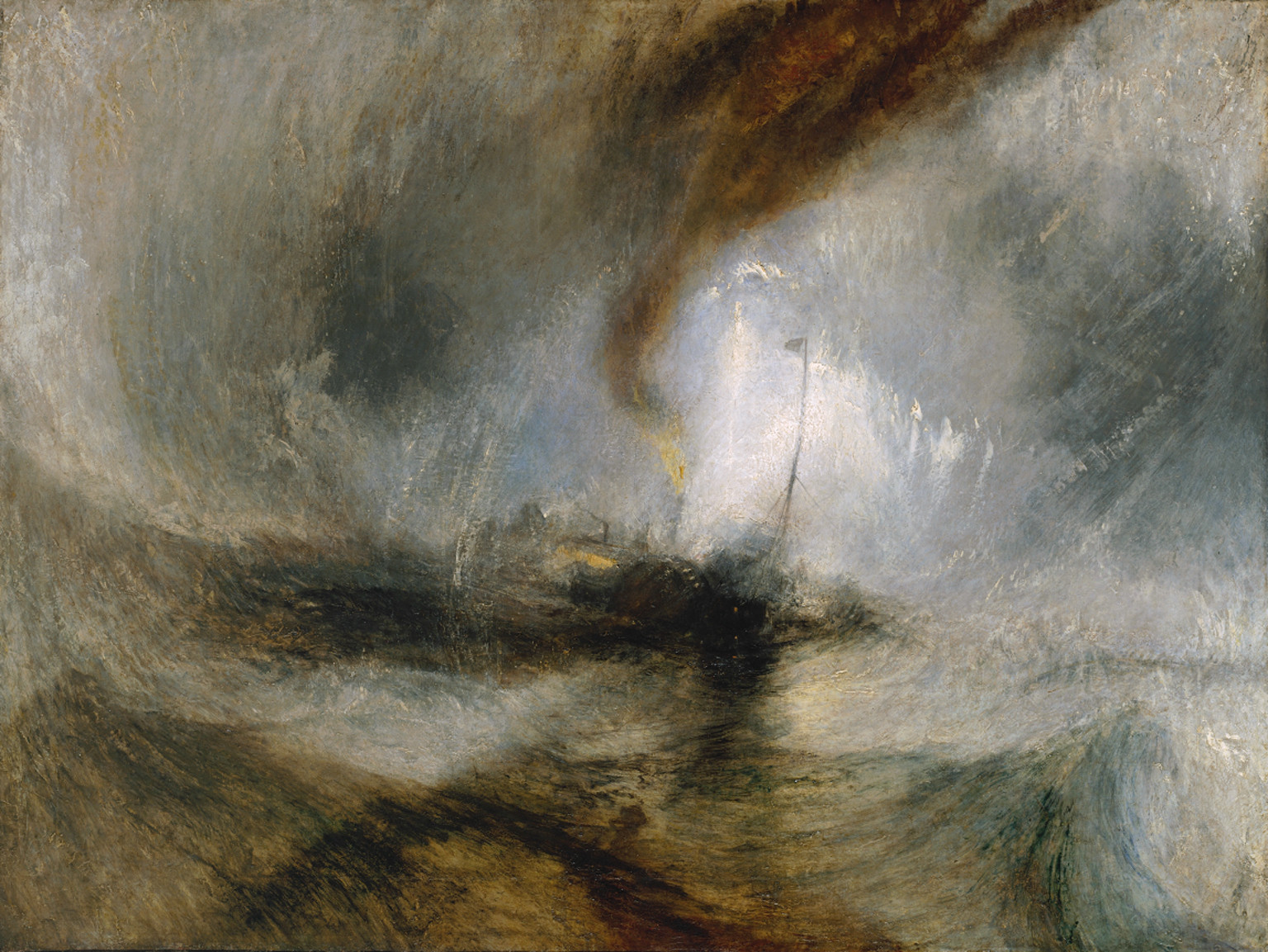

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth, exhibited 1842

As an artist who finds an abundance of content coming from the natural world, I’ve been researching the idea of the Sublime.

This past spring I saw the movie Mr. Turner. It chronicles the last 25 years of the British painter J.M.W. Turner’s complicated life. The scene that stayed with me featured him strapped to the mast of a ship so that he can paint a snowstorm.

The idea of nature being an experience, something that you are inside of, has generated more questions than answers. I am especially interested in how sound contributes to the experience and how I can extract an experience out of one place and share it with people somewhere else. Often that other place is inside an architectural box where people come to have more of a social experience. What does this mean? What’s going on?

Here are some of my notes:

From the Tate’s website: “Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry (1757) connected the sublime with experiences of awe, terror and danger. Burke saw nature as the most sublime object, capable of generating the strongest sensations in its beholders. “

On victorianweb.org George P. Landow, Professor of English and the History of Art, Brown University writes: "Turner and Wordsworth created embodiments of Burke's descriptions of sublimity that make explicit his notion of a subjective, experiential world. Turner's Snow Storm: Steamboat off a Harbour's Mouth (1842), one of the paintings in whose defense Ruskin began Modern Painters, plunges us into the midst of a storm at sea: the whirling vortex of water, sea-mist, and smoke draws us into the scene, making us look not at the storm but through it. The power, magnificence, obscurity, and awe of the Burkean formulation all present themselves as major components of the experience. But again, the viewer, like the painter before him who immersed himself in the storm on the Ariel, does not see these qualities as qualities of an object or scene but as qualities of subjective experience. . .

In other words, in place of the static composition, rational and controlled, that implies a conception of the scene-as-object, Tuner created a dynamic composition that involved the spectator in a subjective relation to the storm. . ."

Sublime Objects by Timothy Morton, published in Speculations Journal and available for free download by Acadamia.edu

A few excerpts: “. . . Heidegger’s essay “language” is about anything but language as a sign for something – more like language as an alien entity in its own right. Language is a kind of object. And language is full of objects. Take onomatopoeia: granted, guns go pan in French and bang in English but in neither do they go cluck or boing. Bang and pan are linguistic contributions by guns. Before they are French and English, they are gunish, and get translated into human. Likewise pop and splat, crack, growl, tintinnabulation and sussurate and even perhaps visual terms such as shimmer and sparkle. Those sorts of words are a kind of sonic translation of a visual effect, the rapid diffusion of light across a moving surface. Shimmering is to light as muttering is to sound. Language is not totally arbitrary. And it is not entirely human – even from a non-Heideggerian perspective.

Then there’s the fact that language always occurs in a medium what Roman Jakobson calls the contact. In OOO-ese (object oriented ontology) this means that objects encounter one another inside another object – electromagnetic fields, for instance, or a valley. When the interior of the object intrudes in some sensual way we notice it as some equipmental malfunction. “Check, check, microphone check. Is this thing on?” More generally, media translate and are translated by messages. We never hear a voice as such, only a voice carried by the wind, or by electromagnetic waves, or by water, or by kazoo. Water makes whales sound like they do. Air and gravity make humans speak certain words in certain ways, Valleys encourage yodeling. . . .

We need an object-oriented sublime in an ecological age. Google Earth wouldn’t qualify as Kantian sublimity – it’s too explicitly scientific. . .

It would be a good start to look away from the supposed “content” of rhetoric, and even away from styles such as metaphor or ekphrasis, and towards the most physical form delivery. Then truly we can say that by generating more sublime objects of tone, pitch, bearing, rhythm, torque, spin, nonlocality, lineation, viscosity, tension, entanglement, syntax, climate, heft, density, nuclear fission, inertia, rhyme (the list goes on and on), rhetoric really does give us a glimpse of real sensual things, things even a cat and an eighteen month year old boy can steal, read about and get tangled up in.”

I am starting to look at language as nature – just another sound. Part of the experience, part of the cacophany, part of the landscape. The need to make sounds that aren’t language is another part of the puzzle. Stay tuned.